Experiments and Results#

This work proposes an approach to train a navigation task in a 3D volume of segmented medical images to find a standard plane visualization, using Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL). The main difference with other state-of-the-art approaches, is the use of a new reward function, based on The anatomical landmarks visible in the currently visualized image. The reward is thus an observable objective.

The last chapter presented a detailed description of the simulation environment and of the proposed agent algorithms that participate in the training process. Moreover, different observations were defined which offer a description of the current state at different levels of abstraction. In the following sections, different experiments will be presented to evaluate the performance of the proposed approach. Different agents as well as different observations will be compared to determine the best configuration for the task.

It is important to mention that the main contribution of this work is introducing the new observable reward function and developing the modular environment, which allows for quick and easy testing of different agents and configurations. This is why the most amount of time was spent on the software development of the environment. The experiments are a proof of concept of the proposed approach that shows the method’s potential. However, the results are not yet optimal and there is still room for improvement.

Computing Resources#

The experiments conducted in this research were performed on a virtual machine hosted by the appliedAI Initiative. The VM was equipped with the following specifications:

GPU: Tesla V100-PCIE-32GB

CPU: 80 cores

Memory: 30GB RAM

The high computational power of the GPU allowed for a faster computation of the training process. The CPU was used to run the simulation environments in parallel. However, computational cost and time were still high, and the training process took several days to complete. On average, to execute 1 million steps of the training process, it took around 3 days. This made it difficult to perform various experiments with different configurations and hyperparameters.

Comparison with RL Benchmarking Experiments#

To understand the scale and computational demands of reinforcement learning (RL) experiments, it’s useful to compare them with benchmark experiments conducted in the Atari domain. Atari games are a popular benchmark for RL algorithms, as they present a diverse set of tasks that require the agent to learn complex behaviors.

Unlike many real-world RL scenarios, Atari environments are fully observable. The observation space consists of frames of the game screen, which provide the agent with complete information about the state of the game. In contrast, the medical image navigation task is partially observable, as the agent can only see the current image and has no information about the rest of the volume.

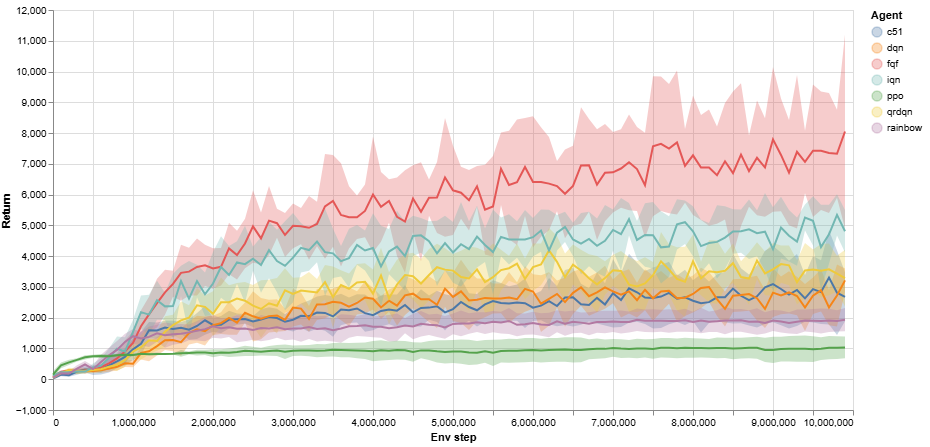

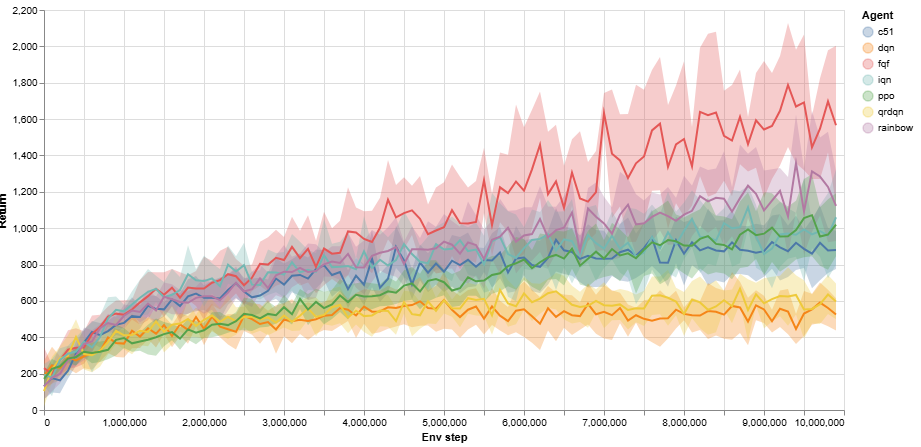

Atari has been maintained and optimized as a benchmark environment for over a decade, allowing researchers to compare and standardize their RL algorithms across a consistent set of tasks. Despite this long history of optimization, achieving convergence in Atari environments remains computationally expensive. For example, to demonstrate convergence, experiments often run for 10 million steps over multiple seeds. Some algorithms, such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which is highly promising in certain settings, may still struggle to converge within this time frame for more complex games. Fig. 26 shows the results of two Atari environments, Seaquest and Space Invaders, used in RL benchmarking experiments from the Tianshou documentation page [1].

This comparison underscores the scale of the RL experiments conducted in this research. Despite the optimized nature of Atari benchmarks, achieving convergence is still a challenge, requiring extensive computational resources and time. In this research, the complexity and partial observability of the tasks, combined with the need to explore a large action space, similarly necessitated significant computational efforts, making the training process time-intensive and resource-demanding.

Random Policy#

To establish a baseline for the experiments, a random policy was implemented. The random policy selects a random action from the action space at each time step. The objective was to compare the performance of the random policy with the trained agents and evaluate the effectiveness of the training process.

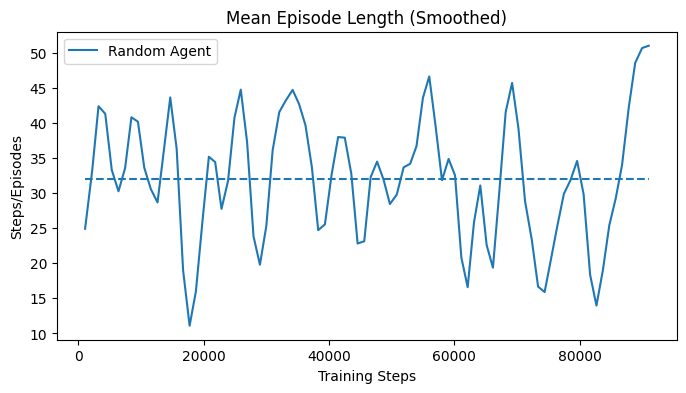

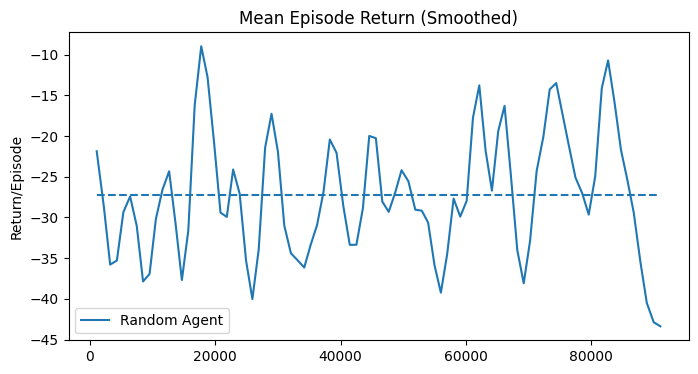

The performance of a random agent was evaluated on 8 volumes, with a maximum episode length of 50 steps and a total of 100 thousand experiment steps. The agent would select in each state a random action from the action space. The average episode length as well as the average episode return oscillate without a pattern. The average episode length throughout the whole experiment was over 30 steps, as shown in Fig. 28.

Dimensionality Reduction#

In order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, a dimensionality reduction technique was applied to the action space. The objective was to reduce the exploration space and simplify the learning process. The dimensionality reduction was performed by projecting the action space into the optimal subspace as described in Optimal Slice Labeling.

1D Exhaustive Search#

A 1D Exhaustive Search experiment was conducted to validate the effectiveness of the reward function and to determine whether it would consistently converge to the optimal reward range, specifically set to \(\delta=0.05\) in the region of the carpal tunnel. This experiment was carried out on four different volumes.

In this experiment, the action space was projected onto the Y-axis translation, simplifying the problem to a single degree of freedom (DoF). The environment was configured to sweep through the entire volume along the Y-axis with optimal orientation. Each step corresponded to a 5 mm movement, effectively conducting an exhaustive search along this axis.

The experiment aimed to observe how the reward function behaved as the agent moved through the volume, and to ensure that the reward consistently reflected the presence of the carpal tunnel within the defined optimal range. For each step, the environment calculated the reward based on the current slice’s anatomical features and checked if it met the termination criterion.

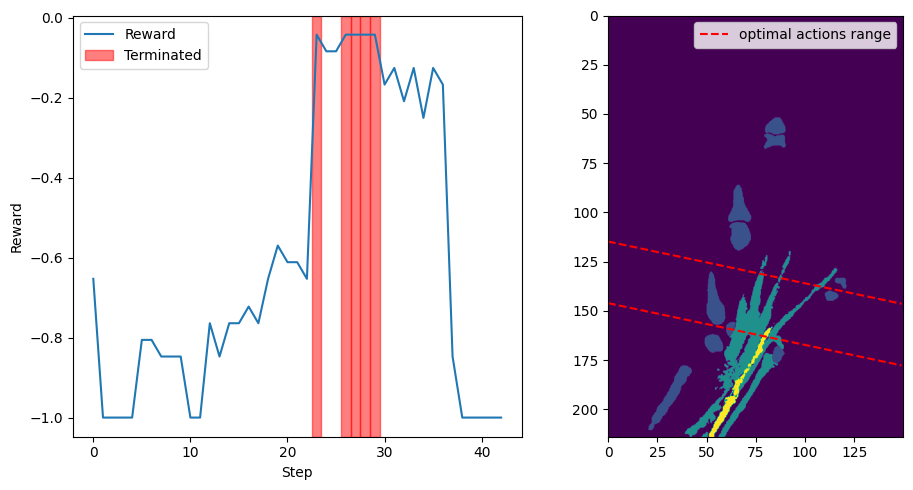

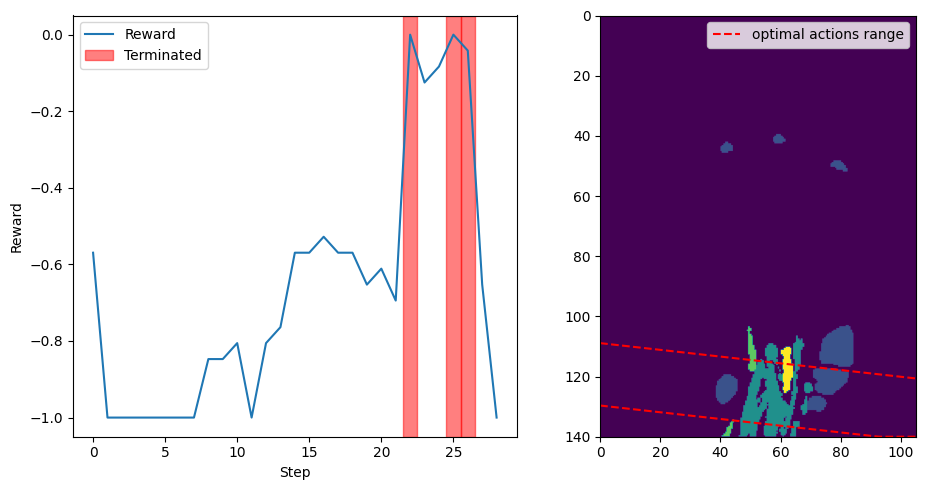

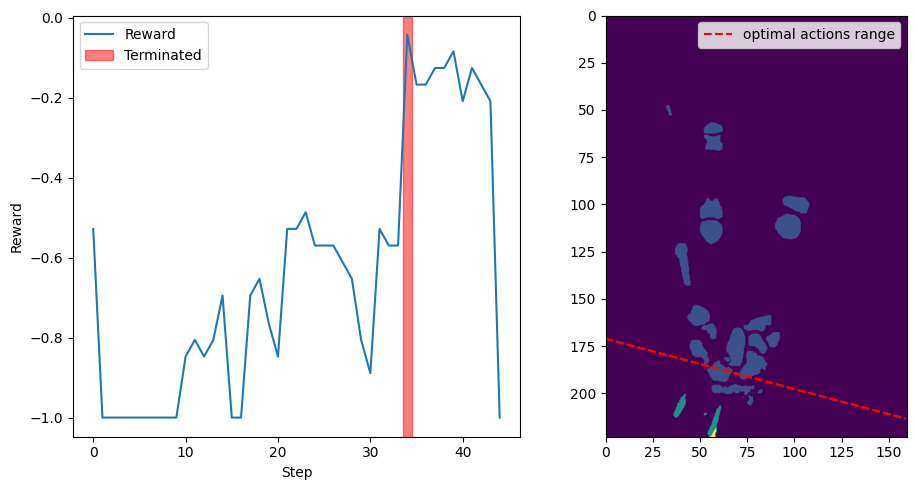

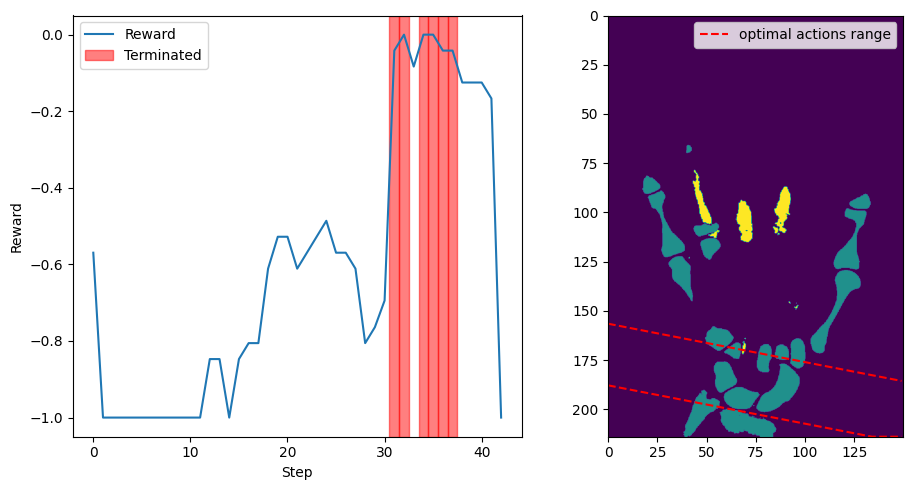

The plot in Fig. 30 illustrates the reward values as the agent moved through the volume. The red-shaded areas indicate where the reward met or exceeded the \(\delta=0.05\) threshold, signifying the presence of the carpal tunnel. The right subplot displays a frontal view of the volume at half depth, with dashed lines representing the first and last actions that yielded an optimal reward.

The experiment confirmed that the reward function correctly identified the optimal region around the carpal tunnel and provided consistent feedback to the agent. This validation supports the use of the reward function for guiding the agent during training and highlights its effectiveness in ensuring the agent converges to anatomically relevant areas.

1D Projection RL#

For the one dimensional case, the action space was projected on the longitudinal axis of the volume. This means that all action parameters where set to optimal, except for the Y-translations. Projecting the action space into a 1D subspace allowed for a simplified exploration process. To make sure that the agent would not overfit to the optimal position for each volume, random transformations were applied to the volumes at every instantiation of the environment, ensuring that the agent had to learn a search policy to find the optimal plane position.

The observation space consisted of the LabelmapClusterObservation, which provides the high level information about the clusters detected in the current slice, merged with the ActionRewardObservation, which provides the information about the current action and the latest reward. The FrameStack wrapper was used to stack the latest 4 observation together, and the best action-reward pair observed during exploration was added to the observation. The agent was trained using the SAC algorithm.

With environment parallelization, different environment instances were used in parallel to train the agent. Since the agent is using the Soft Actor Critic algorithm, the policy is updated off-policy from a batch of collected experiences. The steps’ transitions are collected from the 80 parallel environments and stored in a replay buffer with a size of 1Mio transitions, which means that they can store up to 200 full episodes of 50 steps. The policy is updated every 200 steps. For the policy update, a batch of 256 transitions is sampled from the replay buffer. The V-network, the Q-networks and the policy network are updated using the sampled batch with 2 gradient steps. The first 5000 transitions are generated with a random policy, to fill the replay buffer with some initial experiences, after which the agent collects experiences using the current policy.

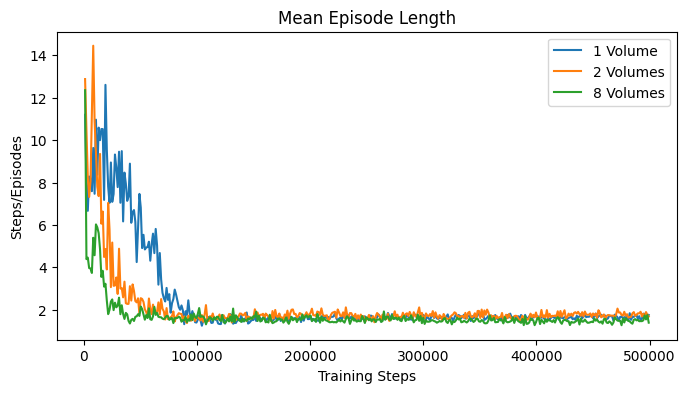

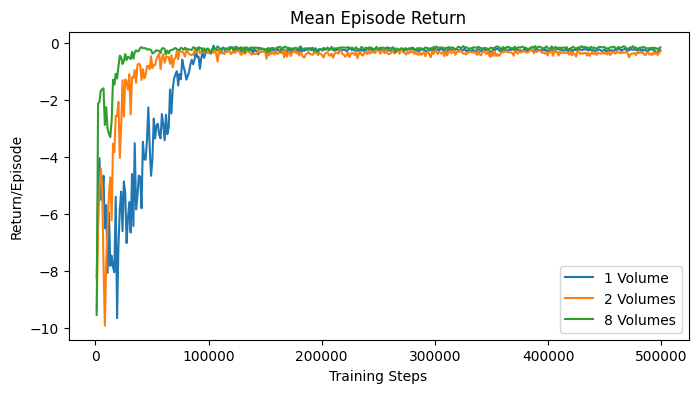

The experiment was first conducted on one volume, with a maximum episode length of 20 steps, meaning that if the agent would not find the optimal plane in 20 steps, the episode would be truncated and a new episode would start. At each episode, a random transformation was applied to the volume, and the initial pose was set in the middle of the global reference frame, which would thus correspond to a different slice of the transformed volume in each episode. The goal of the experiment was to demonstrate wheter the agent could learn to find the optimal plane in a short amount of steps, indicating the ability to learn. The agent converged in around 100 thousand steps to an average episode length of 2 steps.

The same experiment was conducted on 2 volumes, and 8 volumes. The episode length was increased to 30 steps for the simpler scenario, and 50 steps for the more complex one. In both experiments, the agent converged to an average episode length of 2 steps in around 100 thousand steps. The results show that the agent was able to learn to find the optimal plane in a short amount of steps, and it was able to generalize the policy very quickly.

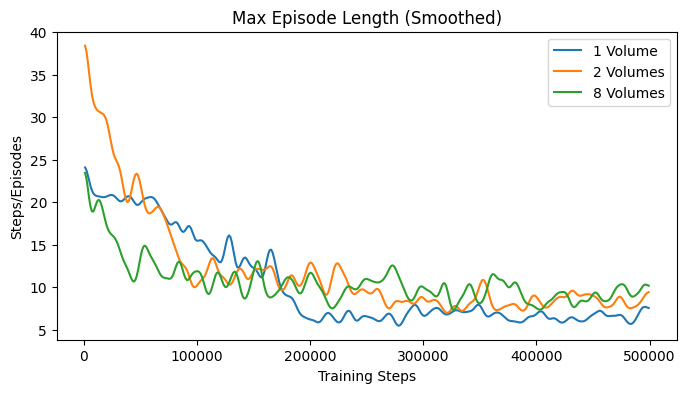

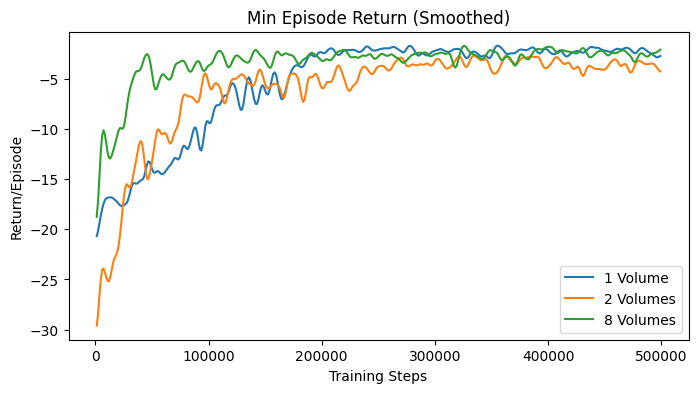

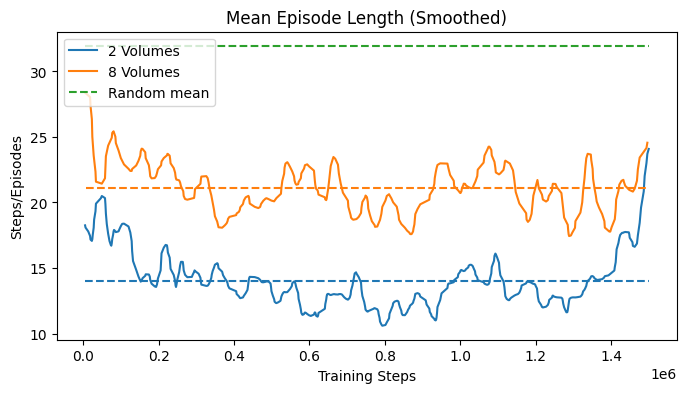

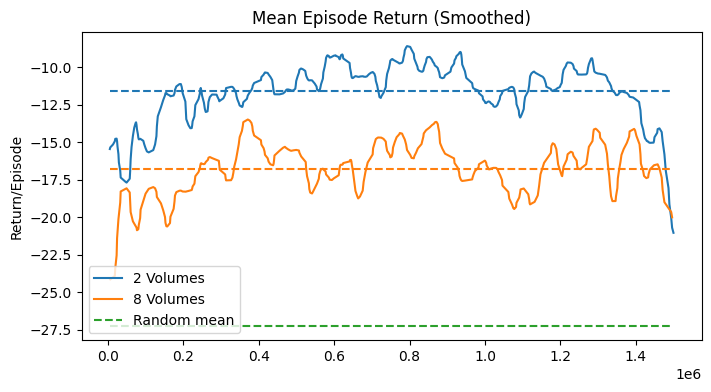

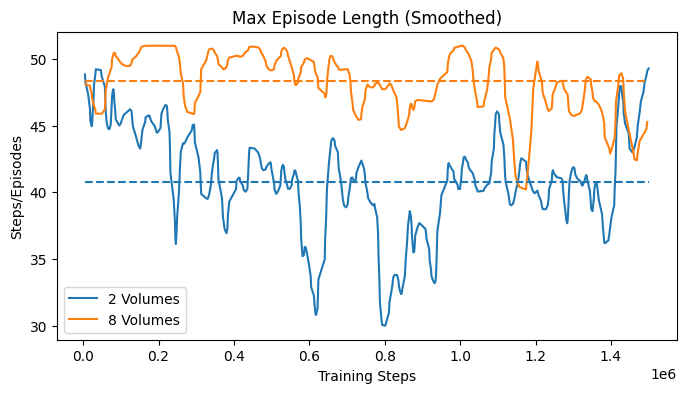

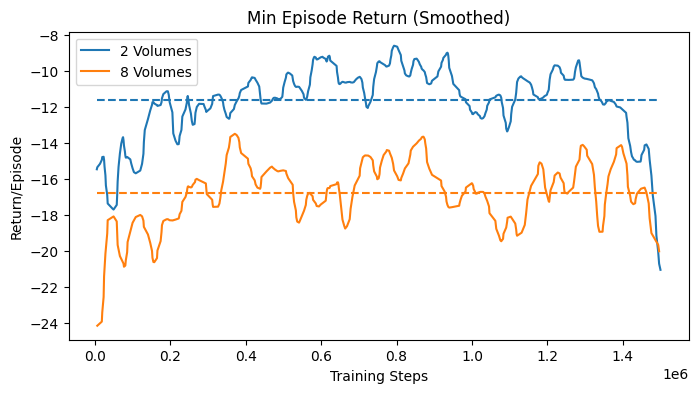

The learning curves in Fig. 34 show some statistics of the training process over training steps. Since multiple agents were trained in parallel, the statistics are averaged over all agents. Each agent would return its episode statistics at the episode end. The first plot shows the average episode length over training steps. The second plot shows the average return over training steps. From these two plots, it is possible to determine the convergence of the agent. The third plot shows the maximum episode length over training steps, and the fourth plot shows the minimum return over training steps. These two plots display the worst case performance of the agents.

2D Projection RL#

The same experiments were conducted on the 2D projection of the action space, which was reduced to the Y-translations and Z-rotations. This allowed the agent to explore the volume with different orientations. The expectation for this experiment is a slower convergence compared to the 1D projection, as the exploration space is much larger, but has better results than those from a random policy. The agent should learn a navigation strategy that leads it to the optimal plane.

The navigation was tested first on two volumes, and then on eight. The episode length was set to 50 steps, all environment and agent settings, as well as the observation space were kept the same as in the 1D projection experiment.

The results, shown in Fig. 38, did not show a significant convergence as in the case of the 1D navigation. However, the mean episode length demonstrates an average perfomance that is better than random search. This indicates that the agent was able to learn a navigation strategy, which was however not robust enough. The maximum episode length and the minimum return show that the agent worse performance would not improve over time, reaching the maximum episode length of 50 steps. This might indicate that the agent was not able to explore enough, or that the observation would not provide enough information.

Best Action-Reward Memory Stack#

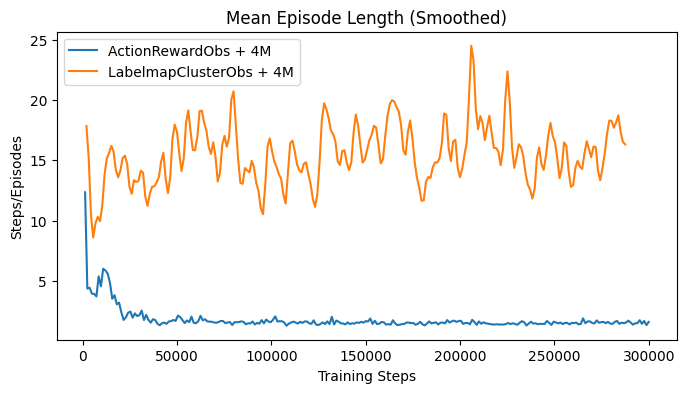

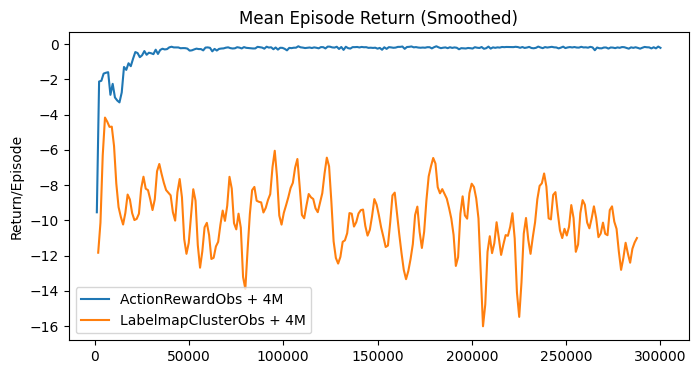

To enhance the agent’s navigation capabilities, the memory of the best action-reward pairs encountered during exploration was expanded from a single memory to the top four experienced pairs. Additionally, the observation stack of the base observation was increased from 4 to 8, providing the agent with more context. This change aimed to help the agent recall the most effective actions leading to the highest rewards, thereby improving its understanding of the volume. Initially, the memory stack was tested on a 1D projection of the action space to assess its impact on performance. However, instead of improving, the agent’s performance declined, as seen in Fig. 42. The issue was resolved by switching the base observation space from the LabelmapClusterObservation to the simpler ActionRewardObservation, which restored the agent’s performance to its optimal level.

The results indicate that the agent struggled to process the combined input of several high-level observations. This included the LabelmapClusterObservation, which captures the cluster information detected in an image, and the ActionRewardObservation, detailing the current action and the latest reward. These were stacked as a memory of the last 8 observations and supplemented by the memory of the 4 best action-reward pairs. All of this information, which is then flattened into a single long array before being processed by the value networks, overwhelmed the agent’s ability to effectively handle the data.

Simplifying the observation data while maintaining a large memory buffer of past states restored the agent’s performance to optimal levels. The reward value itself intrinsically holds sufficient information about the current slice, as it reflects a score based on the clusters detected in the image. This reward information alone proved to be as informative as more complex, high-level data for learning effective navigation.

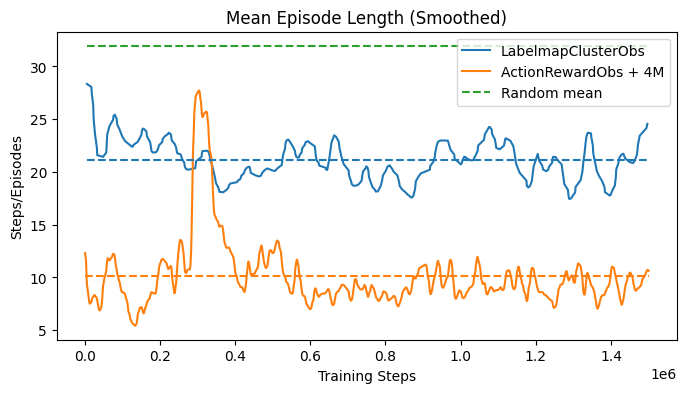

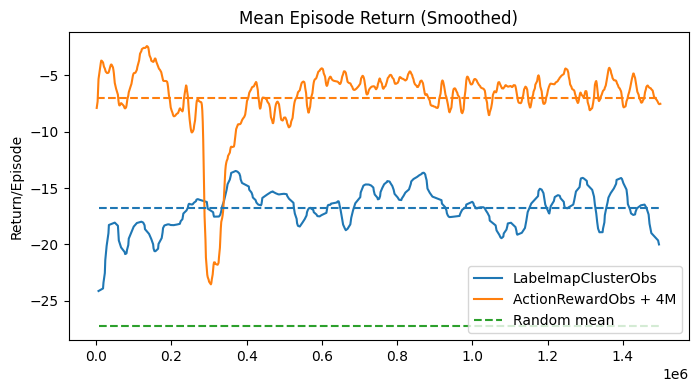

The experiment was subsequently carried out on the 2D projection of the action space, with the expectation that this would enhance the agent’s performance. This time, the results supported the hypothesis, resulting in a shorter average episode length compared to the previous experiments conducted on 8 volumes without the memory stack and with a smaller observation stack, as demonstrated in Fig. 44.

The performance drop observed around 300k steps could be attributed to several factors. These include an increase in exploration driven by the entropy term in SAC, leading the agent to try out new and initially less effective strategies. There may also have been temporary instability in the policy or Q-networks, or shifts in the quality of samples in the replay buffer, which temporarily influenced the agent’s decision-making. As the training progressed, these issues were likely resolved, allowing the performance to recover by 400k steps.

PPO Agent on Image Observations#

An early experiment utilized the LabelmapSliceAsChannelObservation, which includes a channeled image of the clusters detected in the current slice, the current action, and the latest reward (see Labelmap’s Slice Observation). Processing such an observation required the development of a multimodal neural network, which has been described in Customized Multimodal Network. The aim was to provide the agent with full observation of the current slice so that the CNN could learn to extract the relevant features for navigation. The policy algorithm used in this experiment was Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which was chosen because of its balance between performance and simplicity.

The experiment was performed on one DoF along the Y-axis, allowing a long episode length of 100 steps, to encourage exploration. The environment was set up to operate 80 instances in parallel, enabling the collection of diverse experiences across different volume configurations. PPO adjusts the policy on-policy based on the latest batch of collected experiences.

During each training epoch, data from interactions with the environment is gathered and stored in a buffer of 1600 transitions. The policy has been updated after every 800 steps collected from the environment, which allows the algorithm to integrate recent experiences frequently and maintain a responsive adaptation to the learned strategy.

For each policy update, a batch of 80 transitions is randomly selected from the buffer. This random sampling from the buffer introduces diversity in the training data, which helps to reduce overfitting and improve the generalization of the learned policy. The selected batch is then used to compute gradients for updating the policy network. Unlike the SAC algorithm, which uses the entire memory buffer for training, PPO focuses on smaller batches to efficiently manage memory and computation resources. By using only a portion of the buffer, PPO ensures that each update is both manageable in terms of computational demand and rich in diversity, providing robustness to the training process.

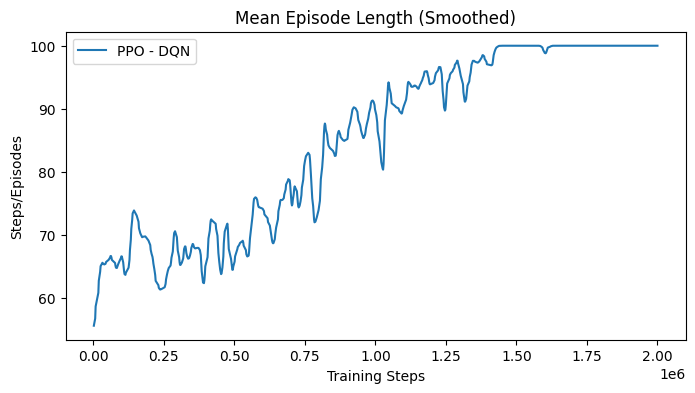

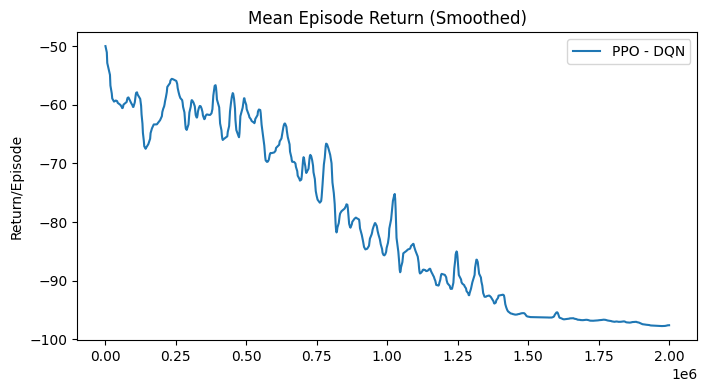

Despite the potential of this setup, the PPO-based policy failed to learn effectively, as evidenced by the degenerated performance where the mean episode length continuously increased. The training results for an experiment on 2 volumes are shown in Fig. 46.

Following this outcome, the focus shifted towards simplifying the observations and considering the use of SAC, which is known for better exploration capabilities, so to validate the approach.

Result Discussion#

In general, the results show that the suggested approach is valid and that the agent can learn a navigation strategy based on the proposed reward function. The 1D projection experiments demonstrated that with a simplified action space, which reduces the exploration space, the agent is capable of finding the optimal plane in just a few steps. This suggests that, with sufficient exploration time, the same architecture can learn navigation in a higher dimensional space.

The 2D projection experiments did not exhibit the same level of convergence, but the agent was still able to learn a navigation strategy that was on average better than a random search. Particularly noteworthy is that adding a stack of the best observed action-reward pairs in the observation space significantly improved the agent’s performance in the 2D projection experiments, where it could find the optimal plane with an average episode length of around 10 steps and an average reward of approximately 5.

However, the experiments also reveal that the agent’s performance is far from optimal. Particularly in the 2D navigation experiments, the agent showed a lack of robustness as it did not improve its worst performance over time. Many episodes were not terminated within the given step limit, indicating that the policy was lost in the volume. That is, it could not infer an optimal sequence of actions based on the current observations. This may be attributed to the observation space not being informative enough or the agent not having adequate time to explore the volume.

As demonstrated in the previous experiments, the approach was explored on a reduced problem using the ActionRewardObservation, which is much simpler but failed to provide sufficient information for a robust navigation strategy in the 2D experiments. The image-based observations LabelmapSliceObservation and LabelmapSliceAsChannelObservation could potentially offer more detailed insights to the agent. However, due to time constraints, further experiments with the slice-based observations were not pursued.

Additional work needs to be invested into making the multimodal network compatible with the best actions memory feature and addressing the memory efficiency issues of the SAC algorithm. In fact, the large buffer size led to memory shortages that caused the experiment to crash, indicating that this issue needs further investigation.

Nevertheless, image-observations hold significant promise, as it provides the most detailed information to the agent. The use of CNNs in this context is particularly advantageous, as they allow for the extraction of complex features that are difficult to capture with simpler array-based observations like LabelmapClusterObs. Further development and refinement of this method are recommended to fully leverage its potential. This method’s ability to enhance feature extraction and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the environment may ultimately lead to a more robust and effective navigation strategy.